Here you go –

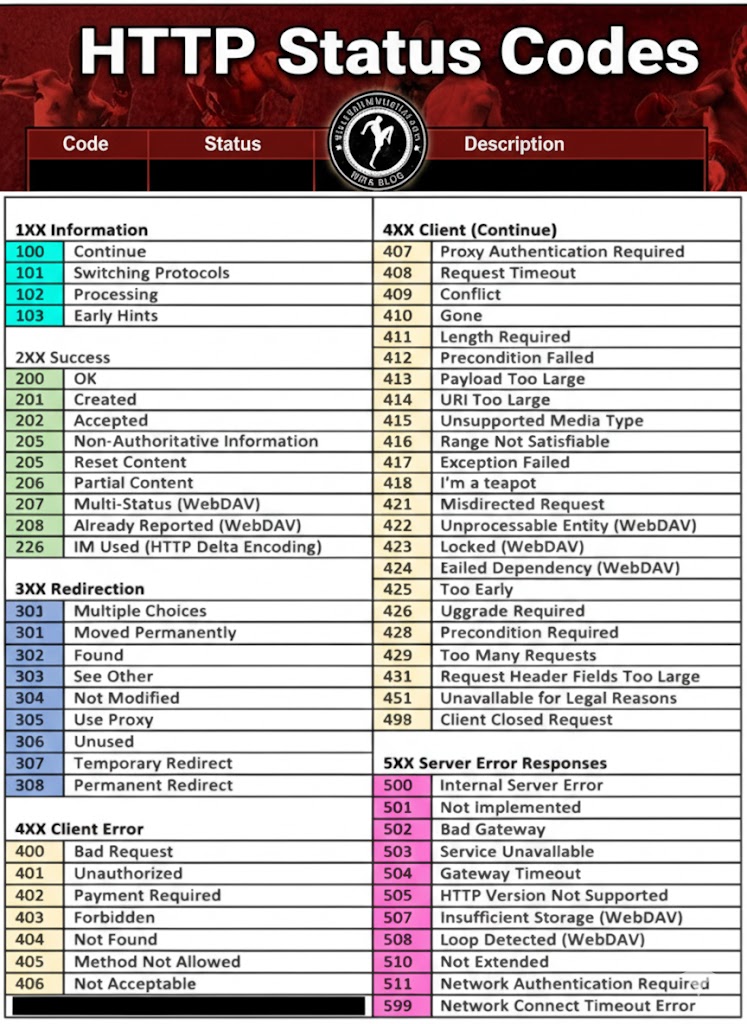

most common – 404 – Not found, 301 – redirect (permanently moved the webpage to this new one)

Ever wondered how Google turns your lovingly handcrafted website into a ranking somewhere below a Reddit thread from 2013? It’s not magic, it’s just a long queue of tiny robot librarians fetching HTML, executing JavaScript, and occasionally having nervous breakdowns when they hit your React app.

This is the life cycle of a webpage inside Google’s digestive system: crawl, render, index, panic. Let’s go step by step before your sitemap starts crying.

Googlebot first has to discover your URLs. That can happen via:

Discovered URLs go into a crawl queue with priority based on things like page importance and your site’s crawl budget.

Before requesting the URL, Googlebot:

robots.txtIf the page or important JS/CSS files are blocked in robots.txt, Google:

Practical implication: Never block

/js/,/static/,/assets/, etc. inrobots.txt.

Googlebot makes a normal HTTP request (like a browser without UI):

At this stage, only what’s in the raw HTML is visible. If your content is 100% client-side rendered (React, Vue, etc.), Google might see almost nothing yet.

Google can sometimes do basic indexing directly from the HTML (e.g. if content is already there), but JS-heavy pages need the next phase.

Google describes the JS pipeline as: Crawling → Rendering → Indexing. Rendering happens in a separate system using an evergreen version of Chromium (a headless Chrome kept relatively up-to-date) called the Web Rendering Service.

After the initial crawl:

This is why people talk about “two waves of indexing” for JavaScript:

Modern research suggests the process is smoother and faster than years ago, but there is still a render queue and potential delay for JS content.

When a page reaches the renderer:

application/ld+json) dynamically Important constraints (from Google’s docs & tests):

noindex, Google generally won’t bother rendering it.Once JS finishes (or time runs out), Google:

This rendered snapshot is what feeds into the real indexing stage.

With the rendered HTML/DOM in hand, Google moves to indexing.

From the rendered DOM, Google:

This is the version of the page that can now rank for queries matching that content.

Indexing also handles:

If Google decides another URL is the canonical, your rendered JS content might be stored but not shown as the main result.

After indexing, the document is:

Because JS adds extra moving parts, a bunch of things can go wrong between crawl → render → index:

robots.txt?page=2, no anchor links), Googlebot may only see the initial “page”. To understand how your JS is being processed:

So there you have it — from lazy bots fetching half your HTML to a headless Chrome pretending to be a real user for 0.3 seconds. Somewhere in that chaos, your content might actually get indexed.

If your JavaScript site isn’t showing up, don’t blame Google just yet — try unblocking your own files and giving the crawler half a chance. Think of it as SEO mindfulness: eliminate obstacles, breathe deeply, and let the bots eat your content in peace.

Explained in simpler terms – How Googlebot Crawls Javascript –

Google finds pages from things you already know:

It puts those URLs in a big to-do list (crawl queue).

Before visiting a URL, Google checks your robots.txt file:

Simple rule for you:

Never block your JS/CSS folders in robots.txt.

Google now requests the page, just like a browser:

At this point, Google has not run your JavaScript yet.

If your important content is already in the HTML (e.g. server-side rendered), Google can often index it right away from this “first wave”.

Now Google needs to know what your page looks like after JS runs – like a real user would see it.

Because this is heavy work, Google doesn’t do it instantly for every URL.

After the first crawl, JavaScript pages go into a render queue:

So for a while, Google might only know the bare HTML version of your page.

When your page reaches the front of the queue, Google loads it in something like Chrome without a screen (headless browser).

This browser:

Then it takes a snapshot of the final page – the “after JS” version.

This is basically:

“What a user would see if they opened your page and waited a bit.”

This is where JS sites often break:

Result: Google’s snapshot may miss your main content.

Now Google has:

From the rendered snapshot Google:

This updated information is used to update your page in the index (second wave).

When someone searches:

If you remember nothing else, remember these:

robots.txt?

The aim here is to –

Verify that product schema (JSON-LD) is implemented correctly on example.co.uk after the migration to Adobe Commerce (Magento).

The script crawls your chosen product URLs and reports if required fields like price, brand, sku, and availability are present.

Click the black terminal icon on the Pi desktop.

python3 --version

You should see something like Python 3.9.2 (any 3.7+ is fine).

sudo apt update

pip3 install requests beautifulsoup4

mkdir ~/schema_check

cd ~/schema_check

nano check_schema.py

Then paste this entire script:

import requests, json, csv, time

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

# ---------- configuration ----------

# Put your product URLs here (you can add as many as you like)

urls = [

"https://www.example.co.uk/example-product-1",

"https://www.example.co.uk/example-product-2"

]

# Fields you want to confirm exist in the Product schema

required_fields = ["name", "brand", "sku", "price", "priceCurrency", "availability"]

# Optional delay between requests (seconds)

delay = 2

# ---------- functions ----------

def extract_product_schema(url):

try:

r = requests.get(url, timeout=15)

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text, "html.parser")

for tag in soup.find_all("script", type="application/ld+json"):

try:

data = json.loads(tag.string)

if isinstance(data, list):

for item in data:

if item.get("@type") == "Product":

return item

elif data.get("@type") == "Product":

return data

except Exception:

continue

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error fetching {url}: {e}")

return None

def check_fields(product_json):

found = json.dumps(product_json)

return [f for f in required_fields if f not in found]

# ---------- main ----------

results = []

for u in urls:

print(f"Checking {u} ...")

product = extract_product_schema(u)

if not product:

print(f"❌ No Product schema found: {u}")

results.append([u, "No Product schema", ""])

else:

missing = check_fields(product)

if missing:

print(f"⚠️ Missing: {', '.join(missing)}")

results.append([u, "Missing fields", ", ".join(missing)])

else:

print(f"✅ All key fields present")

results.append([u, "All fields present", ""])

time.sleep(delay)

# ---------- save to CSV ----------

with open("schema_results.csv", "w", newline="") as f:

writer = csv.writer(f)

writer.writerow(["URL", "Status", "Missing Fields"])

writer.writerows(results)

print("\nDone! Results saved to schema_results.csv")

Save and exit:

Later, open the script again (nano check_schema.py) and replace the two example links with your 10–50 product URLs.

Each URL must be inside quotes and separated by commas.

python3 check_schema.py

It will:

schema_results.csv in the same folder

cat schema_results.csv

or open the file in LibreOffice Calc / Excel.

Example output:

URL,Status,Missing Fields

https://www.example.co.uk/football-goal.html,All fields present,

https://www.example.co.uk/tennis-net.html,Missing fields,priceCurrency availability

https://www.example.co.uk/baseball-bat.html,No Product schema,

delay = 2 to 5 if you test hundreds of URLs (avoids rate limits).| Step | Action | Command |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Open terminal | (click icon) |

| 2 | Check Python | python3 --version |

| 3 | Install deps | pip3 install requests beautifulsoup4 |

| 4 | Make folder | mkdir ~/schema_check && cd ~/schema_check |

| 5 | Create script | nano check_schema.py |

| 6 | Edit URLs | inside script |

| 7 | Run it | python3 check_schema.py |

| 8 | View results | cat schema_results.csv |

That’s it. Job done.

You’ve now got a simple tool that checks your product schema in seconds. No fancy platforms. No monthly fees. Just a Raspberry Pi doing proper work.

Run it whenever you push changes. Catch broken schema before Google does. Keep your rich results intact.

The script sits there, ready to go. Update your URLs. Hit run. Get answers.

This is what proper validation looks like – fast, local, and under your control.

Next steps?

Your structured data matters. Now you can actually prove it’s working.

Go check your products. Then sleep better knowing your schema’s solid.

Questions? Issues? The comments are open. MOFOs

Looking at organic traffic for all our our products containing the word “hygiene” in the product name

Used when you have product variants, like colours and sizes.

Some helmets, call this “product variant schema”. Not sure why though.

Example:

<html>

<head>

<title>Polyester winter football top</title>

<script type="application/ld+json">

[

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "ProductGroup",

"@id": "#footy-top",

"name": "football shirt",

"description": "Nice football shirt for playing football",

"url": "https://www.example.com/footy-shirt",

// ... other ProductGroup-level properties

"brand": {

"@type": "Brand",

"name": "Ace Footy Kits"

},

"productGroupID": "44E01",

"variesBy": [

"https://schema.org/size",

"https://schema.org/color"

]

},

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "Product",

"isVariantOf": { "@id": "#footy-top" },

"name": "Small green top",

"description": "Small wool green top for the winter season",

"image": "https://www.example.com/top_small_green.jpg",

"size": "small",

"color": "green",

// ... other Product-level properties

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"url": "https://www.example.com/top?size=small&color=green",

"price": 39.99,

"priceCurrency": "USD"

// ... other offer-level properties

}

},

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "Product",

"isVariantOf": { "@id": "#footy-top" },

"name": "Small dark blue top",

"description": "Small wool light blue top for the winter season",

"image": "https://www.example.com/top_small_lightblue.jpg",

"size": "small",

"color": "light blue",

// ... other Product-level properties

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"url": "https://www.example.com/top?size=small&color=lightblue",

"price": 39.99,

"priceCurrency": "USD"

// ... other offer-level properties

}

},

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "Product",

"isVariantOf": { "@id": "#footy-top" },

"name": "Large light blue top",

"description": "Large wool light blue top for the winter season",

"image": "https://www.example.com/top_large_lightblue.jpg",

"size": "large",

"color": "light blue",

// ... other Product-level properties

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"url": "https://www.example.com/top?size=large&color=lightblue",

"price": 49.99,

"priceCurrency": "USD"

// ... other offer-level properties

}

}

]

</script>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>

https://developers.google.com/search/docs/appearance/structured-data/product-variants

Here’s an example for boxing gloves –

Possible ProductGroup Schema

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "ProductGroup",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves",

"description": "High-quality BlackBeltWhiteHat boxing gloves designed for training and sparring. Available in various sizes and colours to suit beginners and advanced boxers.",

"image": "https://www.nicemma.com/media/catalog/product/m/e/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.jpg",

"brand": {

"@type": "Brand",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat"

},

"manufacturer": {

"@type": "Organization",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat"

},

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"aggregateRating": {

"@type": "AggregateRating",

"ratingValue": "4.7",

"reviewCount": "83",

"bestRating": "5",

"worstRating": "1"

},

"review": [

{

"@type": "Review",

"author": {

"@type": "Person",

"name": "Sarah T."

},

"datePublished": "2023-09-14",

"description": "Excellent gloves for the price! Great fit and perfect for light sparring.",

"name": "Highly recommend!",

"reviewRating": {

"@type": "Rating",

"bestRating": "5",

"ratingValue": "5",

"worstRating": "1"

}

}

],

"offers": {

"@type": "AggregateOffer",

"lowPrice": "14.99",

"highPrice": "29.99",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"itemCondition": "https://schema.org/NewCondition",

"availability": "https://schema.org/InStock"

},

"hasMerchantReturnPolicy": {

"@type": "MerchantReturnPolicy",

"applicableCountry": "GB",

"returnPolicyCategory": "https://schema.org/MerchantReturnFiniteReturnWindow",

"merchantReturnDays": 30,

"returnMethod": "https://schema.org/ReturnByMail",

"returnFees": "https://schema.org/FreeReturn"

},

"shippingDetails": {

"@type": "OfferShippingDetails",

"shippingRate": {

"@type": "MonetaryAmount",

"value": "4.99",

"currency": "GBP"

},

"shippingDestination": {

"@type": "DefinedRegion",

"addressCountry": "GB"

},

"deliveryTime": {

"@type": "ShippingDeliveryTime",

"handlingTime": {

"@type": "QuantitativeValue",

"minValue": 0,

"maxValue": 1,

"unitCode": "d"

},

"transitTime": {

"@type": "QuantitativeValue",

"minValue": 1,

"maxValue": 3,

"unitCode": "d"

}

}

},

"hasVariant": [

{

"@type": "Product",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves - Pink - 6oz",

"description": "Pink BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves, 6oz size -- ideal for young boxers or light training sessions. Offers excellent comfort and protection.",

"image": "https://www.nicemma.com/media/catalog/product/m/e/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.jpg",

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"color": "Pink",

"size": "6oz",

"sku": "BlackBeltWhiteHat-BG-PINK-6OZ",

"gtin8": "12345678",

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"price": "14.99",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"availability": "https://schema.org/InStock",

"itemCondition": "https://schema.org/NewCondition"

},

"review": {

"@type": "Review",

"reviewRating": {

"@type": "Rating",

"ratingValue": "5",

"bestRating": "5",

"worstRating": "1"

},

"author": {

"@type": "Person",

"name": "Sarah T."

},

"reviewBody": "Brilliant gloves for the price! Comfortable fit and ideal for light sparring."

}

},

{

"@type": "Product",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves - Pink - 8oz",

"description": "Pink BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves, 8oz size -- perfect for training and sparring, offering balanced protection and a snug fit.",

"image": "https://www.nicemma.com/media/catalog/product/m/e/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.jpg",

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"color": "Pink",

"size": "8oz",

"sku": "BlackBeltWhiteHat-BG-PINK-8OZ",

"gtin8": "12345679",

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"price": "16.99",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"availability": "https://schema.org/InStock",

"itemCondition": "https://schema.org/NewCondition"

}

},

{

"@type": "Product",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves - Pink - 10oz",

"description": "Pink BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves, 10oz size -- a versatile glove size suitable for pad work, bag work, and light sparring.",

"image": "https://www.nicemma.com/media/catalog/product/m/e/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.jpg",

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"color": "Pink",

"size": "10oz",

"sku": "BlackBeltWhiteHat-BG-PINK-10OZ",

"gtin8": "12345680",

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"price": "18.99",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"availability": "https://schema.org/InStock",

"itemCondition": "https://schema.org/NewCondition"

}

},

{

"@type": "Product",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves - Black - 12oz",

"description": "Black BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves, 12oz size -- designed for adult training and sparring, providing optimal wrist and knuckle support.",

"image": "https://www.nicemma.com/media/catalog/product/m/e/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.jpg",

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"color": "Black",

"size": "12oz",

"sku": "BlackBeltWhiteHat-BG-BLK-12OZ",

"gtin8": "12345681",

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"price": "22.99",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"availability": "https://schema.org/InStock",

"itemCondition": "https://schema.org/NewCondition"

}

},

{

"@type": "Product",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves - Black - 14oz",

"description": "Black BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves, 14oz size -- suitable for heavy bag work and sparring, offering enhanced padding for protection.",

"image": "https://www.nicemma.com/media/catalog/product/m/e/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.jpg",

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"color": "Black",

"size": "14oz",

"sku": "BlackBeltWhiteHat-BG-BLK-14OZ",

"gtin8": "12345682",

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"price": "25.99",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"availability": "https://schema.org/InStock",

"itemCondition": "https://schema.org/NewCondition"

}

},

{

"@type": "Product",

"name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves - Black - 16oz",

"description": "Black BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves, 16oz size -- ideal for sparring sessions, providing maximum hand protection and durability.",

"image": "https://www.nicemma.com/media/catalog/product/m/e/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.jpg",

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"color": "Black",

"size": "16oz",

"sku": "BlackBeltWhiteHat-BG-BLK-16OZ",

"gtin8": "12345683",

"offers": {

"@type": "Offer",

"price": "29.99",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"availability": "https://schema.org/InStock",

"itemCondition": "https://schema.org/NewCondition"

}

}

]

}

</script>

The above example, was based on this product schema:

Current product schema

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "http://schema.org",

"@type": "Product",

"description": "Best boxing gloves for any level martial arts fighter. Thanks to the range of sizes on offer, these sparring gloves are suitable as adults or kids boxing gloves. Crafted from premium Maya hide leather material, these are long-lasting boxing training gloves. Pink or Black available.", "name": "BlackBeltWhiteHat Boxing Gloves",

"image": "https://nwscdn.com/media/catalog/product/cache/h265xw265/b/o/boxing-gloves-black_1.jpg",

"sku": "BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves",

"url": "https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html",

"brand": "BlackBeltWhiteHat",

"offers": [

{

"@type": "Offer",

"itemCondition": "http://schema.org/NewCondition",

"price": "7.99",

"availability": "InStock",

"priceCurrency": "GBP",

"url" :"https://www.nicemma.com/BlackBeltWhiteHat-boxing-gloves.html"

}

]

,

"review": [

{

"@type": "Review",

"author": {

"@type": "Person",

"name" : "Danny "

},

"datePublished": "2020-08-20",

"description": "These gloves are great- really comfortable and easy to handle. I have got a good amount of use out of these so far and would highly recommend these to anyone looking for a pair of both long lasting and high quality gloves!

",

"name": "Amazing All Round",

"reviewRating": {

"@type": "Rating",

"bestRating": "5",

"ratingValue": "5",

"worstRating": "1"

}

} ]

,

"aggregateRating": {

"@type": "AggregateRating",

"ratingValue": "5",

"reviewCount": "1"

}

}

</script>

Please note:

You want the full productGroup Schema on the “main product” page.

On the variant pages e.g. nicemma.com/mma-t-shirt?red-XL – You still want the ‘normal’ product schema NOT productGroup

“@type”: “Product”

With the details just for the variant.

Good day.

Here’s a brief overview of some of Jung’s essential concepts. Enjoy…

The Structure of the Psyche that big Carl Jung introduced, was a three-part, cool as fuck model that collectively kicked his old pal Fraud square in the ball sack:

Ego: This is our conscious mind, where we keep thoughts, memories, and emotions (those things weak people have) that we’re aware of.

Personal Unconscious: This part holds forgotten or repressed memories and experiences, like the time your ma dropped you on your head when you were 1.

Collective Unconscious: A shared, universal layer of the unconscious that connects all humans. In theory. This could explain why all ancient cultures have similar myths and stories about dragons and mermaids and stuff.

Archetypes: These are universal, inherited patterns of thought or symbolic imagery that come from the collective unconscious.

What does that mean?

Imagine your mind is a big library, and it has books with characters that everyone in the world can see and shares in this library.

These characters show up in loads of different ancient stories, even back in the day when the world was very segregated – because we had to walk or get on a horse to travel places…so people in the Scottish Highlands for example, probably didn’t share information that much with the French. Cos you know, fuck walking that far. Also languages and translating iPhones weren’t all that back in the 11th century.

Despite this, similar myths and stories with similar characters emerged across the world at this, ancient/old time – we’re talking a few thousand years ago. Well a few hundred anyway.

The hero for example, still shows up in modern stories. The hero’s journey – bloke is living day to day life, gets a call to action, kills loads of baddies, discovers himself, goes home.

Jung thought that these similar stories and characters emerged across the world, because of the “collective unconscious”.

Basically, we all have some kind of default programming that we are not conscious of. This is shown in the stories we tell, and they shape how we see the world and possibly, how we classify everyone.

Side note- this sounds similar to “morphic resinence” theory. Which states that when a species learns something new on one side of the world, the new knowledge is somehow used and adopted by the same species then other side of the world.

Examples include: The Mother, The Hero, The Wise Old Man, The Child, The bellend, and The Trickster.

Individuation: This is the journey of integrating both conscious and unconscious elements.

You know that you are aware when someone else is a complete c*nt? Well, we are not so good at being objective with ourselves.

Individuation kinda starts with knowing yourself, your own issues, your traumas, and how you project them.

Individuation is a process of self-discovery – becoming self aware and less of a knobhead that runs on default and auto-pilot.

People need to get to know themselves better, and stop distracting themselves with social media, TV, gaming etc if they want to develop in this way.

Keeping a dream journal can help – as this can, in theory, tell you what your subconscious is processing and ‘doing’. Incidentally, taking l-theanine before bed really gives you vivid dreams.

Understand what triggers you, why you feel the need to do certain things like judge people and get angry.

Face your mother fucking shadow. The part of you that you don’t like and try to hide. Everyone gets jealous, angry etc – this is fine, as long as you don’t act on it. It’s normal, move into and explore these feelings.

Be honest with yourself and accept your faults, so you can then work on them.

Complexes: Often caused by trauma, complexes can be good or bad.

Sometimes seen as clusters of thoughts, feelings, and memories centred around a specific idea within the personal unconscious.

Common complexes relate to parents, inferiority and power/status. Being aware of these complexes can help us grow and be ‘better’. Remember – You are enough and all that, but you can still grow and learn as along as you live.

Jung identified two attitudes and four functions of consciousness:

Attitudes: Extraversion (like attention) and Introversion (likes to be alone).

Functions: Thinking, Feeling, Sensation, and Intuition.

Shadow: This represents the unconscious, often negative or repressed sides of our personality. Lots of memes about this fucker. Probably why you criticise people based on your own insecurities.

Anima/Animus: The feminine aspect found in males (Anima) and the masculine aspect found in females (Animus).

Persona: This is the “mask” or public persona we show to the world.

Self: The central archetype that symbolizes the unified psyche and the ultimate goal of individuation. Key Principles The psyche is self-regulating and always striving for balance and wholeness.

Dreams and symbols play a crucial role in helping us understand the unconscious. The collective unconscious shapes behaviours and experiences across different cultures.

The Jungian Approach to Therapy takes a fresh look at mental health by focusing on the present and future, rather than getting stuck in past experiences. It highlights how crucial dreams and active imagination are for tapping into the unconscious mind.

The goal is to guide individuals toward individuation and self-realization, helping them become their true selves. It also acknowledges the healing power of engaging with images and symbols, which can be incredibly transformative.

Diagram (above^)

Jung’s Model of the Psyche text [Collective Unconscious] | v [Personal Unconscious] | v [Ego] This simple diagram shows the layered structure of the psyche based on Jung’s theory.

At the deepest level is the collective unconscious, followed by the personal unconscious, with the ego sitting at the surface of our conscious awareness. The ego is a right wanker.

Jung’s psychology is all about integrating every part of our personality, including the shadow and spiritual aspects, to achieve a sense of psychological wholeness. His ideas have left a significant mark on the field of psychology, influencing areas like personality assessment (think Myers-Briggs Type Indicator) and dream analysis.

Carl Jung’s idea of synchronicity refers to those coincidences that happen to us when we are more self aware.

Jungian psychologists think that these coincidences connect our inner thoughts & feelings with the ‘outside ‘real’ world, exposing how our minds and the material universe are intertwined.

What is Jungian Synchronicity?

Acausal Connection: Synchronicity connects our internal psychological experiences—like dreams and thoughts—with external events based on meaning rather than a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship.

Example: Imagine a patient dreaming about a golden scarab, only to have a real scarab beetle show up at Jung’s window during their therapy session.

Collective Unconscious: This phenomenon occurs when personal unconscious elements resonate with universal archetypes that are common to all of humanity.

Relativity of Time/Space: Jung proposed that synchronicity reveals a “psychically relative space-time continuum,” where our unconscious experiences blur the usual boundaries of time and space.

(Western Science) | Synchronicity (Jungian View)

Based on cause-effect chains | Meaningful, acausal parallels Governs physical phenomena

Connects psyche and matter Objective, measurable | Subjective, symbolic

How to Generate Synchronicity

While you can’t force synchronicity, there are practices that can help you become more open to those meaningful coincidences:

Heighten Awareness – Pay attention to patterns in your dreams, symbols, numbers, or recurring themes. Example: If you keep encountering a specific animal or phrase, it might be a sign that you’re tapping into an archetypal message.

Engage the Unconscious – Try using active imagination (Jung’s technique of conversing with your unconscious) or journaling to delve into your inner imagery.

Synchronicity often pops up during transitional states, like meditation or when you’re in a creative flow. Interpret Symbolism Look for personal or archetypal meanings in coincidences.

Example: A chance meeting could reflect something unresolved in your emotional landscape. Cultivate Openness Try to step back from relying solely on rational thought; allow yourself to track patterns

Keep a synchronicity journal to spot recurring themes or symbols as they emerge over time.

Clinical and Philosophical Context Therapeutic Use: About 70% of therapists see the value of synchronicity in uncovering unconscious material, although patients often feel a bit misunderstood when they share these experiences.

Individuation: Synchronicity plays a key role in Jung’s idea of self-realization by helping to blend conscious and unconscious elements.

Criticism: Focusing too much on synchronicity can sometimes veer into superstition or delusion, so it’s important to interpret it with balance.

A Modern Perspective Jung teamed up with physicist Wolfgang Pauli to connect synchronicity with the non-local aspects of quantum theory. While it hasn’t been scientifically proven, it still serves as a fascinating tool for exploring the unity of psyche and matter, as well as our search for existential meaning. By being mindful of coincidences and archetypal symbols, people can harness synchronicity’s insights for personal growth and creativity.

As Jung wisely said:

“Synchronicity is an ever-present reality for those who have eyes to see”.

As others say

“Shut up you mad cunt, it’s just coincidence”.

I had synchronicity happen once – which could be just the law of averages, but I dreamt about seeing an old mate in a specific street in Wrexham, and he was wearing a green jacket…this then actually happened a few weeks later. Which freaked me out.

You can scrape reviews if they are :

– In Schema

– Have their own specific class of <p> tag

e.g. class=”review-tex text-base font-secondary”

Yes, you can scrape the reviews if they are formatted in schema markup (like Review, AggregateRating, etc.) or if they belong to a specific class. Screaming Frog’s Custom Extraction feature will allow you to do this.

✅ How to Scrape Reviews in Schema or Specific HTML Classes Using Screaming Frog

1️⃣ Enable Structured Data Extraction (for Schema Reviews) If the reviews are in schema markup (JSON-LD, Microdata, or RDFa), Screaming Frog can directly extract them:

✔ Open Screaming Frog SEO Spider.

✔ Navigate to Configuration > Spider > Enable Structured Data.

✔ Start a crawl, and Screaming Frog will pull JSON-LD, Microdata, and RDFa formats.

✔ Once the crawl is finished, go to Reports > Structured Data > Review Schema to export the data.

2️⃣ Extract Reviews from a Specific Class (e.g., class=”review-text text-base font-secondary”) If the reviews are located within a specific tag that has a class, you can use Custom Extraction to get them:

✔ Open Screaming Frog and go to Configuration > Custom Extraction.

✔ Select XPath or CSS Selector based on your data structure. ✔ Use these extraction methods: 📝 Option 1: Using CSS Selector (Ideal for Class-Based Extraction) css Copy Edit p.review-text.text-base.font-secondary ✔

This will retrieve all tags that have the class review-text text-base font-secondary. 📝 Option 2: Using XPath (For More Complex Queries) xpath Copy Edit //p[contains(@class, ‘review-text text-base font-secondary’)] ✔

This will locate all elements with a class that includes “review-text text-base font-secondary”.

3️⃣ Run the Crawl and Export the Review Data

✔ Start the crawl and allow Screaming Frog to extract the reviews.

✔ After it’s done, go to Custom Extraction > Export Data.

✔ Open the resulting file in Excel or Google Sheets for further analysis. 🚀 Alternative Approach: Scraping JSON-LD Schema Reviews If the reviews are included in JSON-LD schema markup, you can extract them using: Custom Extraction (JSON-LD): xpath //script[@type=’application/ld+json’]/text()

✔ This extracts all JSON-LD data, which you can filter for reviews.

✔ Use JSON formatting tools (like jq or Python json.loads()) to clean and parse the data.

🔹 Summary: Can Screaming Frog Scrape Reviews?

✅ YES, if reviews are inside Schema Markup (JSON-LD, Microdata, RDFa).

✅ YES, if they have a specific class, using Custom Extraction.

✅ YES, if the reviews are static HTML, meaning they exist in the page source.

❌ NO, if reviews are loaded dynamically via JavaScript (use Selenium instead).

| Dev | ChatGPT |

| Usually an arrogant prick with God complex | Is God, or will be |

| Makes you feel like a thick bastard | Very polite |

| Makes you feel like you’re an annoyance | Always happy to help |

| Hates SEO/PPC | Loves everyone – or acts like it anyway |

| Costs about £4k a month to employ | Pro version costs about £10 a month |

| Gets angry at follow up questions | You can ask unlimited follow up questions |

Last Updated – A few days ago (probably)

Having a high-quality, high-traffic blog in the same niche can significantly enhance the organic rankings of an eCommerce site for commercial terms like “buy football goals.” Here’s how:

Search engines such as Google prioritise specific knowledge and expertise. A blog that focuses on football-related topics showcases expertise and builds authority within the niche. This can enhance the credibility of the eCommerce site as a reliable source for football equipment.

If you have 30 excellent, well written, detailed posts about football, then for an array of reasons from topical authority to social shares and backlinks, the eCommerce ‘section’ of your site will tend to rank a lot higher for commercial terms.

Top tip – include your own research and data. People love to link back to statistics. A good example with the NOW Foods 3rd party lab testing of creatine gummies – showing half of them had hardly any creatine in them.

A well-organized blog provides the chance to link to your product pages (e.g., “buy football goals”) using keyword-rich anchor text. This not only drives traffic to those pages but also indicates to search engines the relevance of your product pages for specific keywords.

Blogs tend to attract more backlinks than product pages because they offer valuable, non-commercial content. These backlinks to your blog can transfer authority to your eCommerce site if you effectively link the blog to your product pages.

Blogs enable you to target informational keywords like “how to set up a football goal” or “best football training drills,” which may not fit well on product pages. Once users visit these blog pages, you can direct them toward related products, creating a smooth transition from information to purchase.

High-quality content keeps users engaged on your site for longer periods. This increased dwell time signals to search engines that your site offers valuable content, which can positively influence rankings across the board, including for commercial terms.

Blogs can attract users who are in the awareness or consideration stages of their buying journey. For instance:

A post titled “5 Things to Consider When Buying Football Goals” can inform users while subtly promoting your products.

If they choose to buy, they’re already on your site and more likely to make a purchase.

Anybody can set up a website and sell stuff, and create some ads – but you won’t get direct visitors and people searching for your brand (a HUGE SEO ranking factor) if you haven’t built your brand.

Brand bias is also huge on products – take trainers, football boots and clothes for example. A top quality blog with good content can help build your brand awareness massively.

Marketing bellends call this “thought leadership” and other contrived BS terms to make it sound impressive. But, at the end of the day, if you read a local PT’s blog about fitness and nutrition and it’s amazing, and references meta-analysis and robust research; you’ll probably be inclined to contact him or her if you are looking for a PT in the future? Especially if they display other EAT – Expertise, Authority and Trustworthiness, like a PhD in Exercise Physiology and 20 years experience as a Navy Seal fitness instructor and 10 years as a Premier League Physiotherapy – just to give you a realistic example.

Use search console to see what your blog posts rank for. Take note of any quasi-relevant search terms.

For example, my MMA diet plan, was ranking for Boxing Diet Plan – so I created a new page for this second search term.

In addition to expanding your offerings in terms of content and products, see which are your most popular posts, and if these posts can inspire more content or products. Especially true if the posts related to pain-points of your target audience.